On June 19, 2005 at 0435 in the morning Tehran local time, Northwest Airlines Flight 41 (DC-10 EER aircraft, Ship No. 1243) made an emergency landing at the Meherabad international Airport in Tehran, Iran, the first American air carrier to land in Iran in 26 years. The flight diverted to Tehran, Iran due to an aft cargo fire warning. The resulting maintenance issues were resolved, and operational requirements were addressed on the ground in Tehran, and the flight departed and continued safely to Amsterdam.

This recording with Bo Corby was originally recorded as part of our temporarily-on-hold podcasts, Flight Podcast. Our conversion with Bo remains the only public record of this fascinating incident having taken place.

If you're interested in skipping the introduction, skip directly to the 10m 05s mark in the chapter menu below.

■ ■ ■

Bo provided a case study to us which he approved for publication, and it is reproduced without omission. Images, diagrams, and markings were all made by Bo.

■ ■ ■

Introduction

On June 19, 2005 at 0435 in the morning Tehran local time, Northwest Airlines Flight 41 made an emergency landing at the Meherabad international Airport in Tehran, Iran, the first American air carrier to land in Iran in 26 years.

This report was prepared to review the facts of the incident and relate the story from the eyes of the participants willing to contribute to this report.

Included is an executive summary for quick review. It contains a list of recommendations and/or suggestions resulting from the on site experience.

For those who wish to hear the full story, individual narratives are included. These narratives are written from the perspective of people directly involved in the incident as it unfolded. Diagrams and pictures will help explain and orient the reader to certain information in the body of the report.

Many other people may have been involved and have information to offer however, the collator of this material was not able to determine all the players involved.

Synopsis

NWA Flight 41 was operated with a DC-10 EER aircraft, Ship No. 1243, from Bombay to Amsterdam on June 19, 2005. The flight diverted to Tehran, Iran due to an aft cargo fire warning. The resulting maintenance issues were resolved, and operational requirements were addressed on the ground in Tehran, the flight departed and continued safely to Amsterdam.

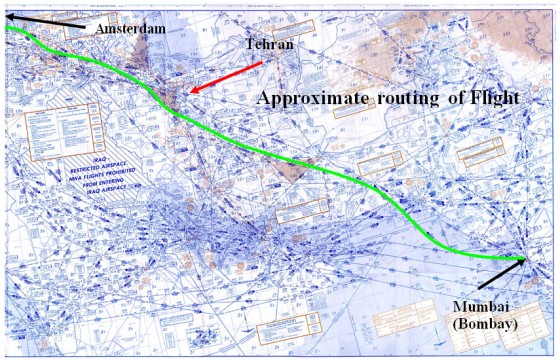

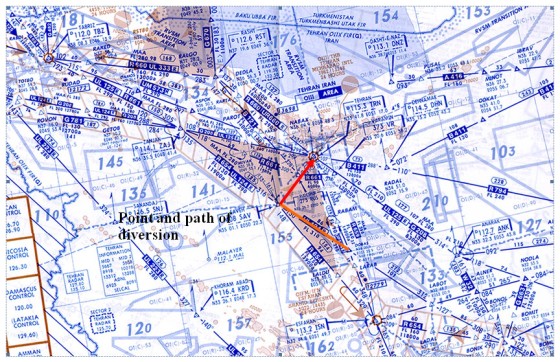

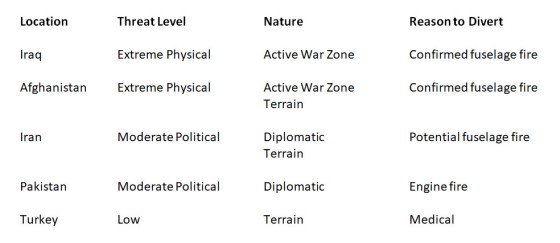

The route of flight was a common routing from Mumbai (Bombay) across India, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey and the European routing to Amsterdam. Below, the general routing through the area where the divert occurred is outlined on the NWA Middle East chart, which supplements the documents used for pilot navigation.

Executive Summary

The following information summarizes the factual events as recalled by the flight crew.

The flight was being operated under normal conditions at FL320, at night, in VMC conditions, with smooth air, and no extenuating weather or mechanical conditions. The flight was southeast of Dobas intersection on airway UL124 at approximately 2240z.

The Captain noticed a momentary illumination of the forward Master Warning light. All cockpit indications were confirmed to be normal. After several further momentary illuminations it was determined that the nature of the Master Warning light illumination was the Aft Cargo Fire-Warning Indicator.

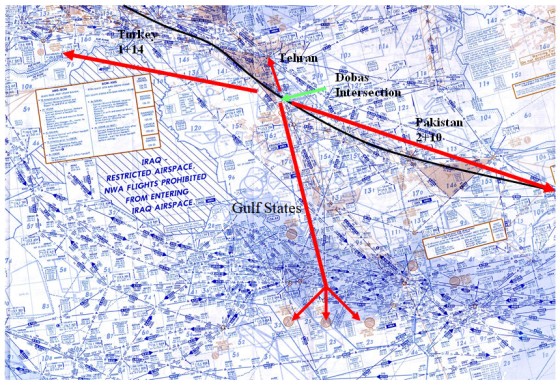

The Captain directed the First Officer to assume flying pilot duties and to research possible diversion airports. The Second Officer gave the “brick” (a package of charts and approach plates to be used for emergency divert situations) to the First Officer. The Captain and the Second Officer began to review the appropriate Red Border Checklist and associated COM procedure (2.26) in order to further analyze and assess the situation. The crew believed at this time that they were possibly dealing with a false fire warning. As a precautionary measure, the flight crew now reviewed the available divert options and noted that MUS in Turkey was 74 minutes away per INS direct distance (525nm), Pakistan was over two hours Southeast, the Gulf States were 1 hour fifty minutes plus and Tehran VOR DME indicated 105nm or about 20 minutes. The First Officer checked the ATIS at Tehran as it was the closest airport and it indicated clear skies, good visibility and light winds.

The Captain contacted the cabin and requested that the Purser come to the cockpit. A flight attendant came to the cockpit, informing the crew that the Purser was on break, at which time the Captain directed that the Purser be interrupted in his break and come to the cockpit, which happened promptly. Concurrently, the Captain directed the First Officer to establish a HF phone patch to MSP Dispatch with the intent that Maintenance Control be consulted. By this time the cargo warning light was illuminating more frequently and of longer duration, which implied a higher probability that the warning was genuine.

Upon entering the cockpit, the Purser was informed of the nature of the situation, including the possibility of a diversion, and to take all of the flight attendants off of their breaks. The Captain and the Second Officer returned to the COM procedure and analysis of the situation, specifically noting the absence of any cargo smoke detector lights in conjunction with the aft cargo fire warning indication. The question arose as to whether the warning presentation indicated a faulty warning system, as there were no smoke lights associated with the fire warning and are taught in training that smoke lights would always be associated with a cargo fire warning.

The Purser was called again and directed to assess the cabin conditions. Concurrently, a weak HF phone patch was established with Dispatch, and a request was made for Maintenance Control in order to trouble-shoot the situation. Upon returning again to the cockpit, the Purser relayed to the Captain that several flight attendants noted a light or faint odor of smoke in the cabin and “more than normal” heat in the floor from aisle 29 right aft. Communications with the company were deteriorating due to HF interference and the opportunity for assistance was unavailable.

Receiving the above information from the Purser, indicating a higher probability that the cargo fire warning was valid, the flight crew proceeded to accomplish the Red Border/COM procedure, including discharging the fire bottle and proceeding to the nearest suitable airport in point of time, which was Tehran (see paragraph below regarding decision to divert). As noted above, the HF phone patch had deteriorated to the point that reception was impossible however, a call was made in the blind to inform Dispatch that the flight was now diverting to Tehran for landing. The Captain resumed ATC communications, declared an emergency and requested permission to proceed directly to Tehran for landing.

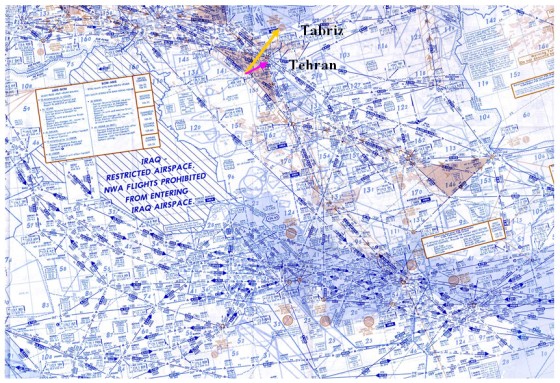

Initial contact with Tehran Control included a Declaration of Emergency and a request for immediate landing at Tehran’s Mehrabad International Airport. This was initially confusing to the controller and they asked if we were asking for landing at Tabriz. Although Tabriz would have been an adequate airport considering airline facilities availability, it was also a former military base and closer to the religious center of Iran. We asked again for clearance direct to Tehran and that we had an emergency. Obviously, they were as surprised as we were and only after several requests were we issued clearance to Tehran. We were instructed to turn right to a heading of 090 degrees and proceed direct to THR VOR when receiving. Subsequent to this instruction, we were re-cleared to the VR Beacon (NDB).

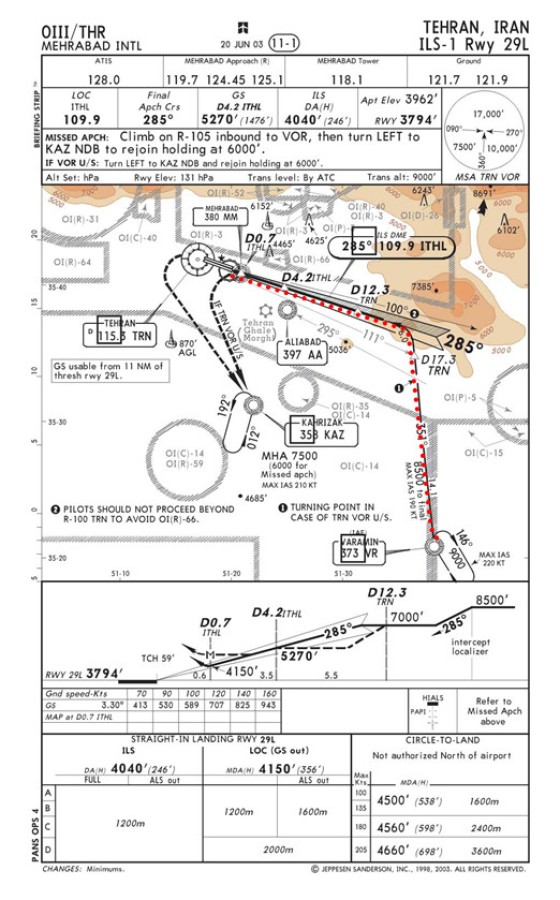

As the aircraft course was set for Tehran, the Captain reconfirmed with the flight crew that Tehran was the prudent option, to which the crew mutually agreed. Clearance was received to begin descent, and the Purser was notified of the decision to divert. During the decent and approach phase the cargo fire warning light re-illuminated several times. In preparation for landing it was required that approximately 70,000 lbs. of fuel be jettisoned, for which permission was requested and received from Tehran control. Prior to landing, the second bottle of extinguisher agent was discharged. After discharge of the second fire bottle we were expecting “smoke detector” lights to illuminate but they remained extinguished, adding to our confusion as to what was going on with the system.

For the fuel jettison area we were instructed to hold south of the VR NDB, as published, which was located approximately 20nm southeast of Tehran. While holding, Tehran control requested the number of passengers on board, and fuel remaining on landing.

The crew discussed the sequence of events that should occur after landing with regard to securing the aircraft and passengers and determined collectively that every effort should be made to deplane the passengers as opposed to evacuating the passengers, if at all possible. The First Officer suggested that the cargo doors remain closed. A request by the flight crew for all available fire-fighting equipment was made. During the hold, procedures, briefings, and checklists were completed for the approach and landing. The Captain reassumed control of the aircraft, and the approach to runway 29L was commenced.

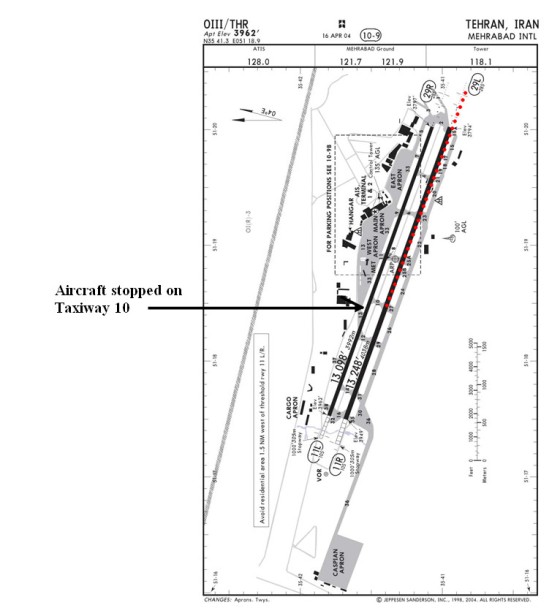

While on the tower frequency, the First Officer asked for the frequency to be used for contact with the fire equipment. We were instructed to remain on the tower frequency after landing. An uneventful landing ensued and the aircraft was stopped immediately after turning off the runway.

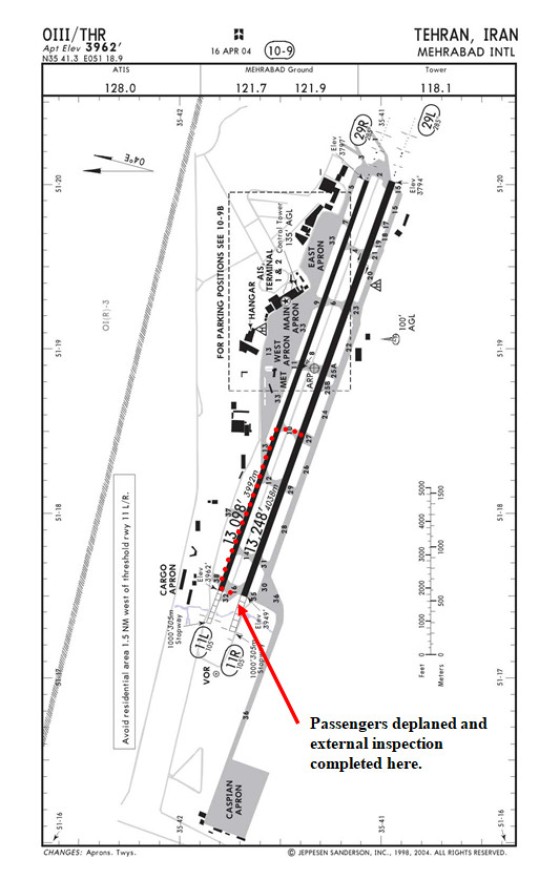

The aircraft was on a taxiway perpendicular to and between runways 29L and 29R, where we were instructed to hold position. An announcement was made to the passengers to remain seated and wait for further instructions.

A requested was made to the tower for a report regarding external indications as to the condition of the aircraft and we were subsequently informed that there was no evidence of fire. The tower then asked for our intentions to which, we requested a taxi to a remote area where the aircraft could be shut down and a proper inspection performed. Instructions were received to cross 29R, turn left and follow the “follow-me” truck to a parking area. A cockpit discussion ensued as to the best disposition of the passengers and Flight Attendants and the decision made to request an air stairs and busses to transport the passengers to the terminal while the aircraft issues were resolved. The tower notified us that an air stairs was enroute to the aircraft. The “follow-me” vehicle instructed us to park the aircraft on the perpendicular taxiway at the far west end of runway 29L.

During taxi to parking the F/O was instructed to again attempt a call on HF for a phone patch to Dispatch. Just as the aircraft was parked the HF phone patch was established. The information received was that the company was aware the aircraft was on the ground in Tehran, there were no pre-arrangements for fuel, assistance would be difficult but, they would contact KLM to see if any assistance was possible and that we were now definitely in an “International Incident” status.

Dispatch offered to call Captain Rob Stewart; the DC-10 Fleet Captain, but there was little help that would be forthcoming at this point. We were on our own for now out of necessity. For all practical purposes, we were “on the moon.”

Psychologically for the crew, the commit point was shutting down the engines, as this allowed people to approach the aircraft. I believe all three of us could attest to the true feeling of isolation and it was certainly a lonely feeling. It was so hard to shut down those engines, as this was our only link to independent power even if we couldn’t takeoff. I believe I turned to my crew-members and said “guys, here we go. As problems arise, we are going to knock them off one by one and focus on departure.” The engines were shut down and then the fun began. It was 0500 local time.

The tower was notified that we were shutting down engines and requesting that a stairs be brought to the aircraft and, that fire fighting equipment standby the rear of the area to monitor the aft cargo area while the passengers were deplaned. Tower notified us they would comply and that a stairs and buses were there to meet the passengers. We asked if it was possible that the passengers be taken to the terminal area until we could resolve the difficulties. The tower responded in the affirmative and shortly after the aft rear passenger door was opened and an official proceeded to the cockpit.

We were just in the stage of completing the parking checklist when the cockpit door opened and a gentleman in a ground staff uniform of Iran Air entered the cockpit and greeted us in broken English. I turned in my seat and greeted the gentleman in Farsi, asking him if he could help us resolve our difficulties. He was taken by total surprise to see that an American airline Captain had any knowledge of Farsi and would make an attempt to speak with him in his native tongue. This action set the stage for a working relationship that carried through the whole experience. We were again asked our intentions and we repeated we wished to deplane the passengers and take them to the terminal while we dealt with our cargo fire situation. The passengers were deplaned very quickly.

The flight attendants were thinking on their feet and had managed to remove all most all of the food and some beverages from the airplane (no alcohol of course) and took it with them to the terminal. While there, they served two full services and cleaned the terminal spotless before reboarding the buses 5 hours later. During the deplaning process, I went outside to survey the rear cargo area to look for any signs of fire or smoke. There was none in the interior, which we would expect their not to be after landing due to depressurization. The aircraft appeared to be secure but we were not ready to open the cargo hold door at this point until the passengers were safely away from the aircraft.

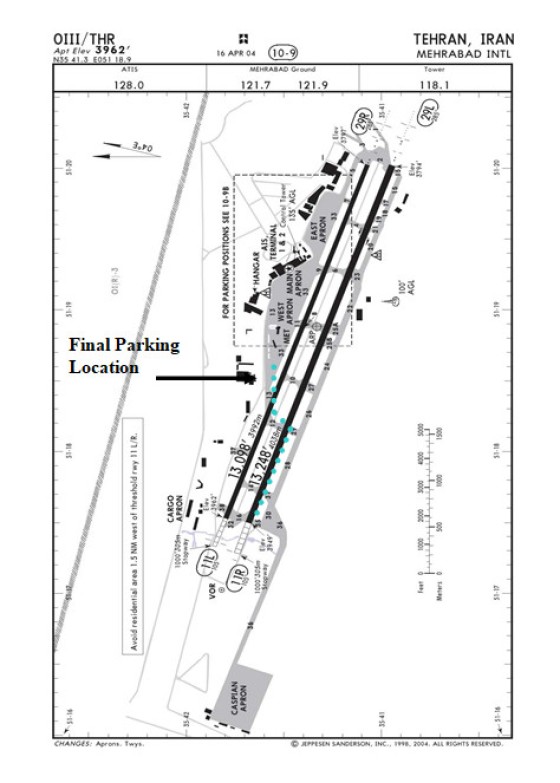

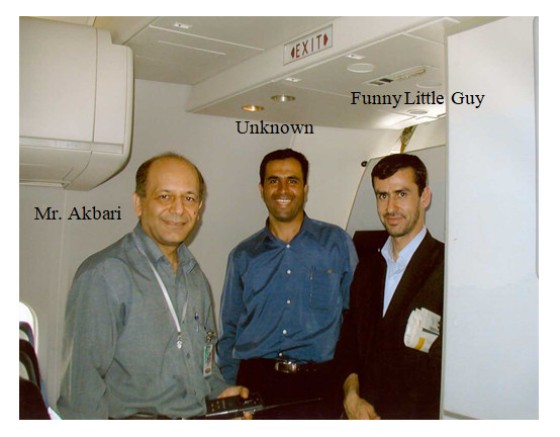

As the last passengers were deplaned another official approached us named Saeed Akbari, whom introduced himself as the Managing Director of Air Traffic Services for the country of Iran. He apparently had a lot of influence because everyone was listening to his directions. Mr. Akbari explained to us that the aircraft was now blocking the runway exit for 29R and they did not have a tug/tractor to move the airplane. Would it be possible for us to taxi the aircraft to another location? Again, I felt some apprehension as to where we would be taken and that the fire issue was not resolved but there appeared to be some urgency in his voice so I agreed to comply so long as the fire units could stay with us until parked and the cargo door opened. He readily agreed to this.

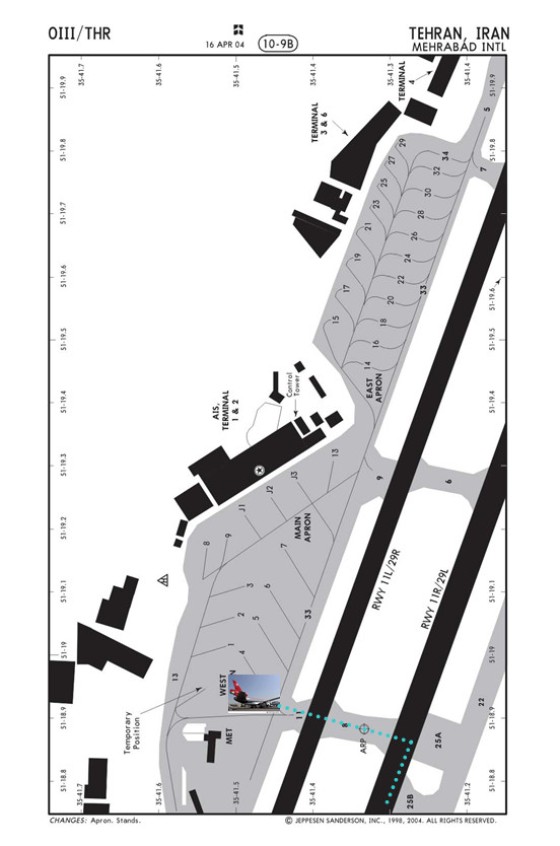

We then taxied the aircraft behind a follow-me truck to a parking stand among numerous other wide-body aircraft. This was good because we were in proximity to their aircraft and if there were any shooting, it would hit their aircraft as well. A stairs was brought to the airplane and other officials were boarding the aircraft. I now know many were there only because of curiosity, as we were a big event in Tehran.

From this point, each crewmember will have a different perspective of the chain of events, as we were all busy with details of resolving our predicament. We had jobs to do and there was little time to interact during the process. Therefore, each crewmember can give a narrative based on their recollections and personal experiences.

The following is a compilation of recommendations/suggestions as a direct result of this experience.

IRAN IS NOT AN OCEAN.

Our publications and company communications continue to tell flight crews that this part of the world should be considered an ocean. Although landing in hostile territory is an undesirable alternative, there are circumstances that would make this a preferable event to other possible choices. The one tool that can best influence an outcome is knowledge and preparation.

We are and most likely will continue to fly over those areas. Assisting the pilots and dispatchers with some training scenarios will aid in reducing stress level of a necessary divert into these areas.

An example might be as follows:

DEVELOP A DIVERT CHECKLIST

Diverts into unknown areas are an extreme exercise in communications, planning, resource applications, coordination efforts, etc. A checklist for the dispatchers and flight crews would be very helpful in applying maximum efforts in recovery operations. If the company intends on continuing flights or increasing flights over these areas, a divert scenario for each area should be examined in advance and a contingency plan with adequate guidance for employees should be developed.

BETTER TRAINING FOR DIVERSION EVENTS OR UNPLANNED GROUND STOPS

Obviously, it is impossible to anticipate what problems a divert situation will bring about. We can however, better prepare our flight crews for these situations by conducting ground training in a group session that explores all possible alternatives through creative discussions and review of actual occurrences, such as the Detroit snow storm or the Moses Lake incident. Combining the dispatchers and flight crews together would be an excellent way to foster creativity and make personnel aware of the impact their decisions have on the operation as a whole.

CELL PHONE AVAILABILITY

The one thing that would have assisted a speed departure is a satellite cell phone to enhance communications. Aircraft satellite communications are not necessary if a cell phone is available. In our case the aircraft satellite communications would have been more restrictive because we were required to leave the aircraft area and needed communications. Each aircraft operating in this theater should be assigned a cell phone with directions on its use. We would have been off the ground at least two hours earlier if a cell phone had been available.

A CULTURE MANUAL

There are short publications available explaining differences in and nuances of Middle Eastern cultures. If forced to land in one of these locations, having a good idea of how not to inadvertently insult your hosts would be a good idea, as there are many ways to do this.

Northwest Airlines has employees who have lived in these areas, speak the languages and who would be a valuable resource in dealing with the events as they unfold in these locations. There should be readily accessible lists of employees who may be of assistance in divert situations and how they may be contacted in an emergency. Knowledge is power and the greatest asset to the captain and crew is being able to anticipate and stay situationally aware.

SUMMARY

Diversions can create bad press and customer un-satisfaction. There are ways to mitigate the impact of a negative event and turn it into a positive experience. Looking at a divert as a “value added” situation can go a long way in retaining customer satisfaction. People realize that things happen to mechanical equipment and have a built-in tolerance for the unexpected. The difference that can be made is how the passengers are handled and flight crews can use more training in this area. We as a culture too often focus on what went wrong... when we could just as easily focus on “what went right” and promote that to the public.

More tools in the above areas will enhance our operating system.

CAPTAIN’S NARRATIVE

Decision to Divert

The decision to divert was the most difficult decision I have ever had to make in 40 years of flying. Although the responsibility was mine to take, it was reinforced by a lengthy discussion with my fellow crewmembers. In recent years there were other aircraft that did not take early action in potential fire situations with catastrophic results, supporting our “better safe than sorry” approach being the most prudent thing to do. In this case we were not sure it was the best decision because of the political realities of the region. Had we chose to continue and if the decision were wrong, we would face many other risk exposures that would jeopardize the safe outcome of the flight. One could not talk their way to safety in flight with a burning airplane, which we maybe could do in Tehran. Tehran unbelievably appeared to be the best of a really bad situation.

Improvise, Adapt and Overcome

The telling of this saga can’t begin without some framework being established. Let there be no doubt, we left Iran because the Iranians let us out! There was no amount of magic involved in convincing them to let us go. It was strictly their decision to allow us continue however, none of us knew any of this at the time and our complete focus was eliminating the reasons why we would have to stay. There were many points where I personally thought we were going to have to stay because of the inability to acquire resources necessary to safely fly the aircraft and passengers out of Iran.

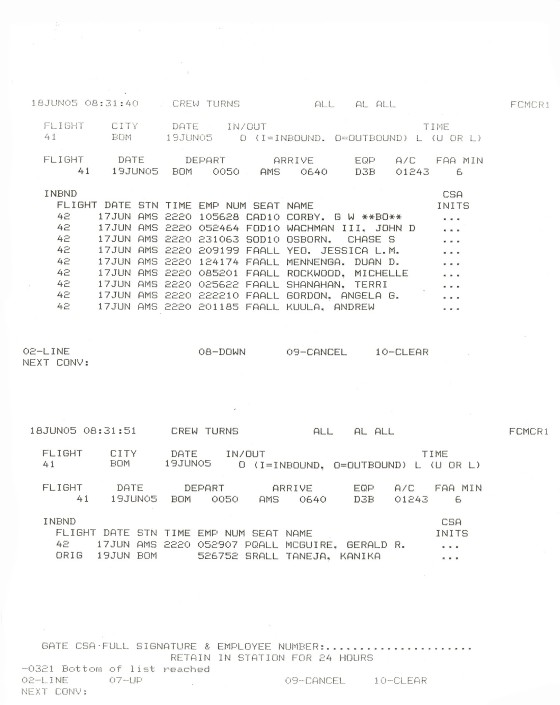

Those who operate on the line understand the psychological effect of crew bonding. Crew bonding occurs when a crew becomes familiar enough with each other that a level of trust in each other’s ability develops and an unspoken communication system allows people to communicate without speaking. This often happens on a subconscious level but enhances the chances of running a smooth operation. Flying with the same crew to Bombay allowed us to become familiar with each other’s capabilities on a previous leg and a certain amount of trust was established and relied upon throughout the ordeal. Our Purser, Jerry McGuire was an old hand and well versed in dealing with unplanned situations. His handling of the passengers was nothing short of exquisite and the fact that we had no disgruntled passengers is a testament to his and the cabin crew’s expertise and determination to make the experience as pleasant as possible. I had no worries on the cabin crews’ ability to handle the passengers and this was a small relief at the time.

Whether it is divine providence or shear dumb luck, the Captain had the fortunate experience of living and working in Iran during the 1970s’, as a pilot for Iran Air and other Middle East airlines. Although some may think this may have had an influence in deciding to go to Iran, the only influence was the fact that it was the closest airport considering the situation and that the facilities for a quick departure most likely still existed. One would understand this only if having lived in Iran. Not a destination of choice. It had been 29 years since I had lived there and 26 years since a US Air Carrier landed on Iranian soil. Iran was to us the best of a poor set of options.

We divided the anticipated job requirements. The F/O, John Wachman III, was the communications link, Chase Osborn, the S/O was the technical guy and I would handle the politics and coordinate services. John immediately tried for a phone patch to keep the company apprised of our progress. Chase began organizing the materials he would need for the cargo door situation, maintenance and fueling, should that ever come.

Our first challenge was the cargo door. In the current world of airline training we are not taught what is assumed we do not to need to know. Pilots never need to open the cargo doors, so we are not taught how to open the cargo doors. The directions are in our manuals but in this case, the manual pages were out of sequence and we couldn’t find them. By this time the ground staff had pulled a belt loader up to the aircraft and by the time we got out there, they were trying to open the cargo door. This was the first of many panics during this ordeal.

Opening the door to a DC-10 may appear to be and is a simple operation for someone who does it daily but, for the flight crew, the lack of familiarity requires some cautions to be observed. There are several door controls to make the door operate and the ground staff was attempting to use them all to no avail. We were able to get them stopped, praying that something was not jammed. Luckily nothing was damaged and Chase eventually found the directions in the Aircraft Operating Manual we carry in the airplane. This enabled us to safely open the cargo door. There were no visible signs of fire but it could have been further in the hold, as there was 36,000# of cargo and baggage on the aircraft.

The next challenge was getting the cargo off the airplane so we could inspect the hold. A belt loader was not going to do the trick but we saw container handlers in the area so began to negotiate for one of those to unload the cargo and baggage. So many people were starting to arrive at the aircraft it was hard to determine who was who at this point. Luckily, Mr. Akbari was remaining in the area and helped getting our needs across to the ground staff.

I had forgotten so much about Iran, having lived there for a year. It was flooding back, the memories. Culturally, the Iranians, or Persians as they prefer to be called, are a proud people with an unspoken desire to be liked as a culture and race. They are a people who are eager to please and take great joy in having an opportunity to showcase their country. Their unwavering hospitality is natural to them and my challenge at this point was to keep them laughing, form a bond as quickly as possible and do absolutely nothing to insult them. This was not an easy trick; as many of our western mannerisms do exactly that, insult them. Showing someone the bottom or heal of your shoe is the gravest of affronts but something we would think nothing of in our culture.

Living in a Middle East culture makes all of your yes-no’s go to “maybe”. There are so many traps in which to fall and unwittingly lose the good graces of your hosts. Getting what you need comes so much quicker when they are shown respect and courtesy. Understanding their culture was pivotal in arranging for a somewhat speedy departure considering the location and political situation.

Before leaving the cargo area, one of the ground staff supervisors assured us the cargo and baggage would be shipped from Tehran to Amsterdam either on KLM or, he said he would send it via Iran Air. For some reason this gave us some level of hope that things were going to work out for the best. We had now been on the ground for approximately 2 hours.

At about that time, Mr. Akbari brought me a cell phone and on the line was the KLM representative in Tehran, whom turned out to be Persian himself. His message was that he would try to arrange for fuel but could make no promises at that time. Not what we really wanted to hear but getting fuel was only one problem and our goal was to make incremental progress, no matter how small. Every time we received something getting us closer to departure, the more we believed we could pull this off.

Shortly thereafter, the ground staff asked if we would like breakfast and informed us that they were assuring that our passengers had food in the terminal. I think my response was that the only food I was craving in Iran was Cello Kabob, the national Iranian dish. They were somewhat impressed with our knowledge of their food. I was told that perhaps we could stay for dinner and if so, they would assure we all received Cello Kabob.

At this point I returned to the cockpit to make an assessment of where we were in the process. Our flight crew meeting identified the remaining things we needed for departure, which were; fuel, flight plan and maintenance. Cargo handling and passengers arrangements were doing well at this point and things appeared to be moving along.

At about this time we started to notice uniforms showing up on the ramp. Not a good sign but curiously, they were not carrying guns. Closer observation revealed they were the Islamic police, keeping a watchful eye on the ground staff to assure no religious laws were being violated. Shortly thereafter I noticed an Iranian staff member on board reading one of the magazines he had found on board that had a scantily clad woman on the cover (a Sports Illustrated swim suit issue I believe, that a passenger had left on the airplane), which sent a shock wave through my heart and stopped my breath for a few seconds. Fortunately, he put it down and I quickly and surreptitiously placed it in the trash bin. Definitely walking through a minefield. We were doing well at this point but there were so many things that could go wrong.

All I could think of at this point was “make them like us” because it would be harder for them to detain us if they liked us. That was certainly thinking in desperation however; it kept us going from step to step. The final goal was too far down the road to think of starting engines but that was going to be a sweet feeling if it ever came. Every person I met was regarded in the frame of what they could or couldn’t do to get us out of there. And I could see my guys in the cockpit... but I couldn’t see the passengers and cabin crew and this was disconcerting. We had to focus on the steps to get the aircraft ready to leave and deal with the rest later. Thank God I had a really good cockpit crew with me that were calm and anticipated our needs extremely well.

The next step was to see what was going to happen with fuel. I left the cockpit to find Mr. Akbari and descending the Airstairs, I noticed it was getting hot outside and there were many people around. This would be a good point to offer some refreshments to the Iran Air staff and other people around the aircraft so I retrieved a tray of sodas and took it down the stairs to pass out. Much to my surprise, no one would accept a soda or anything to drink. The first person to I offered a can of soda refused to accept and I asked him why. His response was that “they will think it is beer”. Then I understood, the people in the uniforms were the religious police and all staff members were under the ever-watchful eye of keepers of the faith. How things had changed in Iran. At about this time one of the ground staff came to tell me Iran Air was going to feed our passengers and would we like something to eat? Once again I told him I was fine but my crew may be hungry. We appreciated them taking such good care of our passengers and I thanked him again profusely.

I couldn’t help but notice, there were so many airplanes coming and going and so many varieties. How could they keep so many 747-200’s flying without the support of Boeing and the US? This was curious, B-747’s, A320’s, A-300’s, TU-154’s, Several other Russian airplanes of numerous types. There was the last passenger configuration B-707, probably the last one flying on the earth. What an incredible site. I asked about Pars Air, a private carrier in Iran in the 70’s and was told it became Caspian Airways, several of whose aircraft were on the ramp. There are 7 new airlines in Iran, sort of like deregulation in the US. The place was the same but definitely changes had occurred in the last 29 years.

At this point, believing fuel was on the way, the next step was how were we going to get a flight plan out of Iran. I asked Mr. Akbari if our company could file a flight plan for us and send it to Tehran somehow. He said no, the Captain had to file the flight plan but to come with him and he would help me make the arrangements. I did not want to leave the airplane but readily saw that this was the only way we were going to get this done so I told my crew I would (hopefully) be back in awhile, I had to file the flight plan. So off I went with Mr. Akbari to the terminal area.

There wasn’t a lot of time to find out things about Iran while we were at the airplane but in his car, we could freely discuss some things I was curious about. The taxi’s in Iran were no longer the Peycan, a type of little car used primarily as taxi’s. There were several taxi systems in Iran, but for the poor man, you used the Peycan. They were painted orange and blue. Orange taxi’s operated North and South... blue taxi’s operated East and West. To hail a taxi, you stood in the street and as a taxi went by, you shouted the name of the location you were trying to get to. If the driver had room and if he was going that far, he would stop. Stopping would occur by locking up the brakes while you ran for the cab. Once you got in, you had to note and remember the amount on the meter and when you got to the perpendicular point to catch the next cab, you looked at the meter again and subtracted the two to determine the fare. Of course, the cab was constantly stopping for people getting in and out and it was much like musical chairs. It took forever to get anywhere. One met a lot of people but it still could be a harrowing experience, especially the “standing in the street and shouting your destination part, as they had to swerve towards you to hear your location. Don’t dare move and don’t make eye contact, as if there is an accident, it would be your fault for distracting the driver. After awhile you adapted to the system and planning allowed time to be set aside for taxi travel in Iran. Mr. Akbari assured me the cars were new... but the system the same.

Our travel across the airport took us to the Iran Air Crew Check-in area, where there were many flight crews preparing for the days flight segments. Mr. Akbari tried to get me in the ATC area but I couldn’t get past security until my passport was checked. This was a big Red Flag. He took me to the immigration officer and I showed him my passport. He asked for the General Declaration form, but it was at the aircraft. As a result, I could not go in the ATC area to file my flight plan. Mr. Akbari asked me to wait in the crew area and he disappeared for about 30 minutes. He returned with an international flight plan ICAO form and an Airbus A-300 flight plan that was filed by Iran Air from Tehran to AMS. He handed these to me and suggested I make it look the same. I looked it over and (without any resources) proceeded to fill out the flight plan identical to the A-300 substituting the DC-10 where it said A-300. The numbers looked close, so I ball parked it and he in turn went to file it for us. I was now beginning to feel we were getting closer to the end game of departure without incident. Unfortunately, there were a few heart stoppers remaining.

On the drive back to the airplane we discussed family and the hope our country’s got back together again. He said most people in Iran like the United States and wished things were not the way they are at present. One thing he related was the appreciation he had for the assistance the US provided during the earthquake they had that killed so many people several years ago and that he had been looking for a way to repay us for our kindness.

Back at the airplane things were coming along. Chase had the cargo off and it disappeared to a location unknown to us but with the offer of putting it on KLM or Iran Air to AMS. I went up to the cabin and met one of the head ground staff in the cabin. He said “Captain, the aircraft needs servicing, I can do this for you.” I said “malesh” (which means never mind in Farsi) it would be fine, but he insisted. He said he could make the cabin look like new airplane. I could see he was proud of this work, so I said ok, let me see. He said, “No charge Captain, we fix good” and that he did. When they were finished, the cabin was sparkling. I think our passengers were quite surprised when they later reboarded.

Then came the next “crisis”. A ground staff supervisor came on board and said “Captain, we have bad news, there is no fuel.” If anything ever gave me this pause, this was it. I said ok, do you take credit cards. Chase and John were right there with their credit cards as well, but the response was no, this is Iran, no credit card. This was not a good thing. He said we would have to try something else to get fuel.

One of my first thoughts was how the airline would deal with our taking a collection from the passengers. I had actually heard of that happening many years ago and to get out of there, it would be a last resort alternative.

A few minutes later outside the aircraft, I told him, I could pay cash. He said, “Captain, you have cash”? I said yes, and pulled out $ 60.00 and offered it to him and said I would like $60 US Dollars worth of fuel. He said he didn’t think we would get very far on $ 60 and I said, I know, but it will let me start one engine and we like to take problems one at a time. He laughed heartily and said “malesh (meaning never mind) Captain” and disappeared for about 45 minutes.

We next saw him in the cabin; he had a list of SITA addresses for Iran Air. He asked if NWA was an IATA carrier and if so, they were to send a “promise to pay” conformation message to the addresses he had given us and we could have fuel for departure. That was a major relief but we still had to rely on John to get the message across to Dispatch and ask them to concur with the appropriate messages to Iran Air. This was no easy task for John with the communications deteriorating the way they were as the sun came up.

We now had a flight plan (we hoped), and a fuel truck was on its way (we prayed it was true). Then came the word from the funny little guy (more on him later) that I had to meet with some very important people and talk with them. This seemed like an odd request but nothing so far had really been normal, at least normal as we know it. Setting this request aside for now, I went to check on John and the communications for the fuel guarantee. He was having a time with the HF but was able to get off a message with the addresses the company was to send the guarantee, so things were looking up. What we wouldn’t have given for a cell phone!

After some time, the fuel trucks began showing up, meaning John was successful and the idea worked. The trick now was getting the fuel trucks positioned to dispense the fuel. I had a funny feeling about this, especially when we observed the fuel trucks approaching the aircraft from the rear. The fuel dispensing station on the truck was at the rear and at the top of the tanker. It was a platform of obvious fixed height, with hoses and controls to dispense fuel. The truck was a tractor and trailer arrangement. Because of this, the best approach would be drive under the wing from the rear, outboard to inboard. But, there are different rules of logic in Iran.

The first time I came to Iran in 1975 I arrived at 3:30 in the am. It was snowing and I had pre-arranged friends of friends picking me up at the airport. I would be living with them until I found a place on my own as quickly as possible. I distinctly remember them preparing me for every day life in Iran. The most profound statement they made was “forget your sense of logic... logic is different here... it’s Iranian logic”. The solutions to problems are found in a different place, and you have to learn to accept that it will work out eventually, just give them their space.

This was evident the next morning after my arrival. I woke around 10:00 am to the sound of a car spinning its tires on the icy streets. I got up and looked out the window to see a small car with its front wheels in a depression in the snow, perpendicular to a street onto which they were trying to turn after stopping. Eventually they quit trying to move the car and got out and opened the trunk. They took out a jack and proceeded to jack up the front of the car, placing burlap bags under the front wheels, trying to make the front end level with the street. One person got back in the car and put it in reverse while the others went behind the car and pushed forward. If they weren’t so serious, it would have been hilarious. I dressed quickly and went down to help. I took the burlap bags out from under the front wheels and laid them out in front of the rear wheels and got in the drivers seat and rocked the car until the rear tires grabbed hold of the burlap and drove out onto the street. Iranian logic.

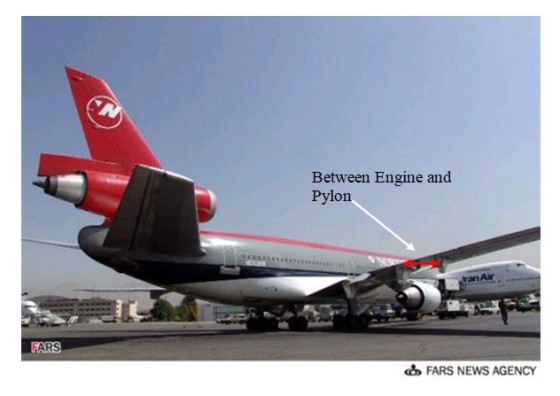

The Iranian solution to the fuel truck positioning problem was logical considering they either didn’t want to move the ground equipment (for some reason) or approach from the outside of the wing, driving inboard to the fueling panel. The decision was made by the driver to drive behind the aircraft and pull the truck between the engine and flap pylon from aft to forward. Not a bad idea except for the fact there was only about 3 feet clearance on either side of the tanker and the engine or pylon and once through the opening, he had to turn the truck to his right to get the rear of the tanker close enough to reach the fueling station on the aircraft, also moving the read of the tanker very close to the pylon. NOT a good plan but it was what it was and we didn’t have a lot of choice.

The first pass didn’t work and he had to come around again for attempt two. This time he was closer but not close enough so a third pass was required. What is interesting and at the same time frightening, was that each time he came through, (threading the eye of the needle) he had 4 people on the ground telling him to do different things. It was really scary because if he had hit the engine or pylon... the aircraft was not leaving that day... or maybe never.

Fortunately, the third time was a charm and it worked, we now had fuel. Only then did we discover the other fuel truck was there because this truck positioned did not have the required 50,000 pounds of fuel we needed. They wanted to do the same procedure on the other wing but I asked that they use the same side so Chase could monitor what was going on. Frankly, I couldn’t watch it again for fear of having a physical event. But it all worked, we had fuel. What a relief this brought us, as we were now closer to leaving. This thing was coming together at last.

As the fuel was being dispensed, Chase remained at the fueling station on the truck to assure the proper procedures were being followed and the correct amount was being added. While returning to the cockpit to determine the next requirement, Mr. Akbari informed me he was required to attend a meeting and was leaving one of his department supervisors to continue our assistance in preparation for departure. In my mind I thought of him as the funny looking guy and I never got his name. He was always smiling though so we dubbed him as the “funny little guy”.

It was then one of the most personally amazing events took place, the arrival at the next parking stand of Iran Air aircraft tail number IR-RBT, a B-727-200 that I had personally flown when employed by Iran Air. It was not only still in use but looked brand new in all respects. It was a surreal experience that generated an intense desire to look at the aircraft... one more time. I asked if it would be possible to visit the crew prior to their departure for home. Security was consulted and permission granted for me to walk to the aircraft and converse with the crew.

The B-707 we observed earlier was the last passenger aircraft in worldwide service. That was mental time travel to see it taxiing by our aircraft. But to see RBT again, this experience was on the level of meeting a mentor who was instrumental in making your life what it is today. I was 24 years old when living and flying in Iran, not only was the flying experience shaping my preparation for an airline career, but also my worldview was being shaped by the experience by living under a totally different culture. The experience was changing my understanding of the concept of the meaning of truth and how what it true is dependent of the belief of the culture you are making this determination within. The only thing I could relate it to was meeting a friend who died many years prior and suddenly learning they were not only not dead, but standing in front of you beckoning you to come and visit. It was a majestic sight understandable only to the two parties involved. I had to see this airplane one last time. This was a family reunion of sorts.

The crew of RBT could not have been nicer. I was given a tour of the aircraft and offered something to drink with apologies there was no food remaining on board. Sitting in the cockpit thinking of all the characters I flew with in Iran came flooding back. Jessie James... (American and his real name), Gunter Rollfe (German), Frank Roberts (Australian), others too numerous to mention and then Iranian pilots, who you always addressed as Captain; Captain Dagestani (who had three wives and gave me marital advise on the virtues of only one wife), Captain Marwan, one of the most wise of pilots I had come across at that stage of my young career. Many more I remember their faces but their names have slipped into the sea of lost memories.

We were departing Tehran to Shiraz, a late night short turn with an aircraft less than half full of passengers. The Captain (Marwan) elected to raise the fuel amount to full... all tanks. It was only a 40-minute flight to Shiraz so I was a bit curious as to why we were carrying so much fuel. I had to craft my question carefully, as not wanting to appear to question the Captain’s decision. I waited until we were leveled off enroute and gingerly asked why so much fuel was required for the short hop to Shiraz. Captain Marwan turned slowly to me and said, “well, Bo, maybe when we get to Shiraz, the lights are out, this is Iran (meaning an electrical failure at the airport and at that time in Iran, it was not uncommon to loose electrical power in the cities from time to time). I thought about this and it seemed like a reasonable explanation. Shortly thereafter I again took the chance of asking a question without challenging or appearing to challenge his authority, which in Iran, was absolute. I said, “ but Captain, it is only a 40 minute flight back to Tehran, so we still have much more fuel than we need” and he slowly turned again and looked at me with a slight hesitation (danger sign) and said, “yes Bo, but when we get back to Tehran, maybe the lights are out”.

A pilots experience is nothing more than a collection of moments of insights gained over time and Iran taught me much in the short time I spent there.

The crew of IR-RBT was relatively young did not remember any of the pilots I flew with in Iran, most likely many of them escaping Iran during the revolution or retiring years before they came up the ladder in the airline. It was a beautiful experience.

Back at the aircraft the fueling was complete and my crew was ready to tackle the maintenance issues and getting the logbook prepared for a legal departure. Having reviewed the MEL and the complications with the signoff, it appeared to be a task that could become daunting, as finding a mechanic to perform a signoff on our aircraft would need the proper authority to do so. I was not worried about the expertise issues; there were just too many aircraft there with incredible diversity. This was going to be a diplomatic problem that had to have a solution. What we wouldn’t have given for a cell phone! Being relegated to the HF, as the sun got higher the communication with the company was becoming impossible and we were not able to get a clear and lasting phone patch with Dispatch.

In the cockpit the guys were researching the maintenance issues we would have to deal with to depart legally. We needed a mechanic and one who could sign off the aircraft logbook and release the aircraft under the MEL. Only one problem... no DC-10’s in Tehran and the mechanics there have type-ratings on aircraft types, not unusual for the Middle East and Europe. The procedure we would have to use was somewhat complicated with a lot of paperwork but, Chase and John had a good handle on it so the challenge was to find someone willing to do the work.

Miraculously, an Iran Air mechanic showed up on the airplane asking what he could do to help us out. I explained to him that we needed to have the cargo area inspected and the logbooks signed off prior to departure. He said there was a problem because he did not have a type rating for the Delta Charlie One Zero (DC-10). I then asked him if he could show me his Iranian Engineers License, which he did. Listed on his License was the B-727, B-747, Airbus 300/320, TU-154 and other various aircraft including the British Trident. I explained to him that with his expertise, it was not going to be a problem because of the vast experience he had was more than adequate to make us comfortable. All we needed him to do was inspect the cargo compartment and give us his opinion and judgment as to the cargo compartment being safe for departure (the theory here was one step at a time, perform the work first, worry about the paperwork later). He again said he never worked on the aircraft so I asked him if he liked working on the Trident. He looked at me funny and then I told him the Douglas airplane was built similar to the Trident... many pulleys and cables!! He laughed at this and said he thought it would be ok if the S/O would be with him. We assured him we would be there with him every step of the way, the whole time.

John was communicating with the company and someone in Dispatch was actually anticipating some of the things we needed such as, the aircraft sign-off and had arranged FAA approval to allow us, the flight crew, to do the paperwork in this special case. This was a Godsend, as it solved the problem of having the Iran Air mechanic signing off paperwork, which could have been a difficult approval to obtain. Fortunately the company had anticipated this and received special approval from the FAA allowing the pilots to sign the paperwork on behalf of Maintenance Control. Nonetheless, completing the paperwork took considerable time, as we were unable to hear the Maintenance Controller on HF more that a few words at a time. We sure could have used a cell phone for this event. At lease 45 minutes was expended trying to interpret the HF transmissions. Three people had to listen and two writing.

It now appeared we were going to finally pull this thing off. The next step was retrieving the passengers and this would be the final test to determine if our technical/emergency stop was going to succeed. I approached our liaison ATC gentlemen (the funny little guy) and asked if it was possible to send the passengers. One of the Iran Air ground service leaders was within earshot and came over and asked if they could groom the cabin. The cabin was a shambles but I didn’t want to delay. He said he wanted to do the cabin, empty the trash bins and groom the pax cabin and we could see it was either a gesture of good will or maximizing the revenue. In either case, we weren’t in much of a position to refuse, things were going so well and he said not to worry about price, he would do it for free. I accepted their hospitality with many thanks and they did a superb job of cleaning the aircraft. Once that was complete, we again asked for the passengers and they said the passengers and crew would be on the way in a few minutes.

It was then I was asked to come outside the aircraft and meet “someone important”; whom they had earlier said would be arriving at the aircraft. I agreed and going outside the aircraft the next shock was seeing a crowd of people and TV cameras everywhere. I stopped in my tracks and asked the liaison what was planned with the TV crews, wondering how I was going to get out of this one without insulting them; we were so close to leaving. No doubt we were going to be on Al-Jazziera

Obviously, our ticket out of Iran included an interview on camera. There was not much to do but accept so I said OK, but I need to know the questions before I agree to an interview. He said they just wanted to know three things, why we came to Iran, how we were treated by ATC on landing and how Iran Air treated us as an emergency situation. He also asked that if we were able to put in a good recommendation for the ATC services we received, he would be most grateful. I explained to him that I could do all three things but the questions had to be restricted to those items, to which he readily agreed.

The interview was exactly as he indicated it would be. We gave glowing compliments on the handling by ATC; the service received from Iran Air was outstanding; and that my company, crew and all of our passengers were extremely grateful for the wonderful hospitality received from the Iranian people in Tehran. While we were completing the interview, the busses showed up and the passengers began boarding the aircraft.

The last passengers were boarding and I had many people to thank and say goodbye to, as did my cockpit crew. In the midst of all this activity, my liaison came back up the ramp and asked for “three Americans with passports”. This sent chills down my spine with visions of a hostage situation in progress. Why three Americans and their passports? I knew I had a Jewish flight attendant on board and this was a cause for major concern.

The approach I took was to inform them that I had a crew duty time problem and had to leave immediately or I would be put in jail on arrival back in the US for duty time violations and the time was now critical. Although he expressed regret for my pending troubles, in a nice way he assured me this would expedite our departure. So, I asked him why he needed three Americans and he explained they wanted to ask the passengers if they would tell the TV crews the kind of service they received at the hands of Iran Air while in the passenger terminal. What a relief that was.

I asked him to give me a few minutes and went into first class, explaining to the passengers we needed three volunteers to give a testimonial regarding the treatment they received from the Iran Air staff while they were in the terminal, but to restrict their statements to only that subject and no other without my specific approval. Every passenger volunteered, so we picked three and the interview went off without a hitch.

After the testimonial passengers were on board, the door was closed and we were on our way to Amsterdam. Iran Air pushed us back to the start position and disconnected the tug. Engine start was commenced, the appropriate checklists completed and taxi was initiated for takeoff from runway 29R. Once airborne, we made several attempts to advise the company we were airborne via HF. The continuation of NWA Flight 41 to Amsterdam resulted in a landing at approximately 2:30 pm local time, to the great relief of the passengers and crew.

First Officer's Narrative

The First Officer was not able to submit a report due to other commitments while this was being prepared.

Second Officer's Narrative

Final Approach

I felt the reality of our situation on final approach to Mehrabad International Airport, Tehran, Iran. All normal and emergency checklists and all procedures were complete regarding our aft cargo fire warning indications. I was confident that our potential cargo fire was under control. I was also confident in our decision to land in Tehran as being the safest course of action. We all felt that it was safer to ask questions on the ground rather than in the air regardless of potential political ramifications. Still, there admittedly were intense feelings of trepidation regarding our decision and as to what may lie ahead for us. Up to this point, our dilemma had almost felt like a simulator training session. It was all very surreal! As with any aircraft emergency, we had dealt with our situation in a methodical, step-by-step process but we were soon to face the unknown predicament of landing in a potentially (hostile) and unknown country with no checklist to follow from this point on.

We touched down in total darkness at 0430 local time and I remember how impressed we all were by the vast number of emergency equipment vehicles with all of their lights flashing awaiting our arrival. Our first priority after stopping the aircraft was to ensure that there was no (external) sign of fire, which was confirmed by the emergency fire equipment personnel. Once we taxied to an assigned safe area, I managed to establish a brief HF phone patch with MSP SOC to inform them we were safely on the ground in Tehran and a status report would be forthcoming. The parting words from our dispatcher at that time were, "This is now an international incident, good luck", as he signed off. We all felt very isolated at this point! There was an obvious uneasiness amongst the crew as the engines were shut down while awaiting contact with the Iranians.

I noticed the aft cabin door was first opened which led me to open the cockpit door as we finished the parking checklist. An employee from Iran Air entered the cockpit and greeted us in English. Captain Bo Corby, who had flown for Iran Air one year before the Iranian Revolution of 1979, returned a greeting in Farsi. This greeting came as a complete and pleasant surprise to the official and helped to establish a working relationship with the Iranians that ultimately would turn into a strong bond between supposed hostile foreigners by the end of the day. Bo's knowledge of the country, the language, its people, and their culture would turn out to be, in my opinion, the main reasons we would ultimately be allowed to leave Iran in a timely manner.

We expressed our intentions to have our passengers deplaned and brought to the terminal and to complete our assessment of the aft cargo area for any (internal) signs of fire. It was our desire to not introduce any oxygen into the cargo area while passengers were on board at the recommendation of our First Officer, John Wachman. The Iranian official seemed quite obliged to honor our request. Several (modern) busses arrived a short time later and our passengers deplaned via air stairs and boarded the busses. Our cabin crew of flight attendants smartly removed the majority of food and beverage items to take into the terminal. I'll admit that I did not want to separate the cabin crew from the flight crew as I still had concerns about our overall safety at this point. It was, however, decided that they should remain with the passengers, which turned out to be a good decision. This allowed our flight attendants to serve our passengers but more importantly help alleviate their fears and feelings of apprehension. We had an outstanding cabin crew led by our Purser, Jerry McGuire, which continued to meet and exceed the needs and expectations of our passengers throughout this whole ordeal. Shortly thereafter, our flight attendants and passengers were transported to the safe and comfortable (air-conditioned) confines of the passenger terminal.

Still unsure of how things were going to play out, and now isolated from our cabin crew and passengers, we were asked to move the airplane to another area on the airport. This request sounded an internal warning regarding the Iranians' objectives for us and raised concerns about where we were to be taken. Of course, we still had the (internal) aft cargo fire issue to contend with but we were told that would be addressed once we arrived at the desired parking location. We taxied our aircraft behind a "follow-me" truck toward the airport terminal and near numerous Iran Air wide body aircraft. The fact that we were not being repositioned to a remote sight, away from passengers and potential witnesses, brought great relief to the anxiety I was still feeling. Air stairs were brought to the forward cabin door and numerous officials and airport employees enplaned to meet us.

One Hoop At A Time

Almost instinctively, the crew as a whole assessed our overall needs and began working at our own areas of expertise to help expedite a potential departure. We were completely unsure of when this might happen or how things would progress, but hopeful nonetheless. Bo coordinated various operational aspects such as flight planning and fuel requirements while campaigning to numerous officials for our eventual release. I cannot overstate the incredible job our Captain did in getting the Iranians to honor our numerous requests. His interaction with them was nothing less than masterful. John would maintain HF communications with MSP SOC and provide excellent recommendations to remedy potential problems throughout the day. I would oversee technical issues regarding cargo removal, refueling, and maintenance.

Our first task, after repositioning the aircraft, was to open the aft cargo door for further investigation into any signs of a fire. This seemingly simple task proved somewhat problematic, as I had never had any hands-on experience in opening the cargo doors, as we are not trained to do so. I wished I had been taught this on O.E. I ultimately had to return to the cockpit and refer to the Volume II (systems book) as there are several door panels and controls on the DC-10.

Numerous Iran Air ground staff were now gathered around the aft cargo area and indiscriminately pulling control handles as I returned with the system's pages in my hand. This caused great alarm, as we were afraid they might have damaged something. Fortunately, they did not and I was able to direct the proper procedure to open the door. There were no visible signs of fire but there was a need to remove all 36,000 pounds of cargo/containers for a complete inspection (per the MEL, as we had fired all cargo extinguisher bottles). Once this was done, it was confirmed that our aft cargo fire warning had, indeed, been a false warning. We were assured that our passenger's luggage would be shipped to Amsterdam via KLM or Iran Air and we were encouraged that progress was being made.

Next, preparations were made for flight planning and fuel as the Captain was escorted to the operations area of Iran Air. John and I continued to assess our situation and upcoming needs trying to stay one step ahead of the game. We monitored the offloading of the cargo, researched maintenance issues and talked with numerous Iran Air support staff. I talked briefly with some about politics, their culture, and was told how they wished things could be different between our two countries. Some of them had visited the U.S. and many had family members here. Several workers had driven by just to get a look at us and would smile, wave, or give a thumbs-up as word had spread that Americans were on the airfield. They spoke English very well and I was amazed at how friendly everyone was and how eager they were to help us.

The Captain returned to tell us that a flight plan had been filed and that fuel was on its way. The support staff had offered to clean the cabin (which they did), service the airplane with water (which was not needed), and had informed us that our passengers had been fed and they even offered us a meal, which we politely declined. We really felt like things were falling into place.

The fuel trucks finally showed up as did more and more officials. The fuel trucks were not, however, making their way to our aircraft and I noticed the Captain shaking hands with more and more people. This caused concern that our progress was being impeded by higher ranking officials. Bo was doing a tremendous job maintaining his composure, as there appeared to be a snag with fuel being delivered to us. Understandably, they wanted confirmation that payment could be made for the refueling of our aircraft and this created quite a lengthy delay. We all offered to pay with credit cards but that evidently was not an option, as credit cards are not accepted in Iran. Arrangements were ultimately made to their satisfaction by NWA through a Teletype promising to pay the fuel bill.

Then came the difficulty of actually getting the fuel trucks into position to refuel with extensive ground equipment and cargo containers around our aircraft. It seemed that we had tackled each problem by having a direct hand in solving the problem or at least being able to offer some input for a successful outcome. However, this important piece of the puzzle seemed to be out of our hands as they were not receptive to our recommendations and created another point of anxiety.

The refueling staff seemed to have their own ideas on how to get the truck into position without having to move any ground equipment. This might have worked if there had been one person in charge of directing the others. However, each member of the team seemed to have their own ideas on how to successfully guide the fuel truck to the refueling panel under the right wing. Unfortunately, the lone driver was taking directions from two or three guide men to turn the truck left, right, forward, and to backup all at the same time! This scenario would have been fairly humorous to watch except that they came dangerously close to hitting the number 3 engine/pylon and wing fairings several times which would have kept us there indefinitely. Numerous passes and attempts were made while we held our breath for a successful outcome. With the truck finally in position, I was able to direct and monitor the procedure from the truck's refueling platform. We finally got our fuel and it seemed we were getting close to departing.

The final issue remaining was clearing the maintenance logbook write-ups. This presented a problem, as there were no DC-10 qualified mechanics on the airport. John was in HF contact with SOC to explain our dilemma. We had been granted a special FAA waiver to allow the flight crew to sign of the logbook under the direction of NWA maintenance control. This task proved extremely cumbersome, as HF reception was very poor. Statements had to be repeated as we drudged through line by line. It took all three of us to complete this paperwork but eventually finished some forty-five minutes later. A final inspection was made to ensure the cargo compartments were empty (per the MEL) and we were ready for the passengers to reboard.

The busses arrived with our cabin crew and passengers who seemed to be in good spirits. I made a final Walkaround inspection while saying goodbye to several workers from Iran Air. I shook hands with a few who had been the most helpful to us and thanked them for their hospitality and assistance. The Iranians we met were friendly and gracious and could not have done more for us. As I was completing my Walkaround, there was a larger than normal crowd now gathered around our Captain near the base of the air stairs. He, evidently, had been asked to give an interview for some news agency with television cameras involved. Although, I did not know the context of the interview, it appeared that Bo had charmed them once again, as he had the whole day.

The last passenger was boarded, the cabin door was closed, and we were soon to be on our way to Amsterdam a little more than six hours after we had touched down in Tehran. This relatively short time on the ground was a real testament to the entire crew working together as well as the Iranians allowing us to successfully depart. Flight 41 landed safely in Amsterdam at approximately 14:30 local time after more than eighteen hours on duty.

Purser's Narrative

I was taking my crew rest sitting on a folding chair at door one left when F/A Dew Mennenga informed me that the Captain wanted to see me in the flight deck right away. Although Dew seemed quite calm I immediately wondered what emergency I might find. Upon entering the cockpit, Captain Bo Corby informed me that they were getting an intermittent cargo fire warning light in the aft cargo compartment. He asked me to go back and check the floors and walls in the aft galley and the aft passenger cabin for smoke and heat. I asked him if I should awaken the cabin crew on first break and he said yes.

On my way to the aft galley I informed the crewmembers in the forward and mid galley of the situation and woke up the crewmembers on break near door 3 left. In the aft galley I pulled out the meal carts and felt the floors and lower sidewalls for heat and did not discover any hot spots or smell any smoke. On the way back up the left aisle I smelled the faint odor of smoke at floor level in the area of row 29. The floor also felt warmer than normal in that area. I proceeded to the mid galley and asked Michelle Rockwood, the Main Cabin Coordinator, to come back to Row 29 with me and I asked Terri Shanahan and another flight attendant to check Row 29 on the right aisle. Meeting back in the mid galley all four of us confirmed that we smelled smoke and the floor seemed very warm at row 29 on both aisles.

I proceeded immediately to the flight deck and informed the flight crew that four of us smelled smoke near the floor at Row 29 on both aisles and the floor was warmer than usual. The Captain informed me that we would proceed in the direction of Tehran and request permission to land there. He said that we were approximately thirty minutes from Tehran and about one and a half hours from a military base in Southern Turkey. He further stated that it would be very busy in the flight deck and that they might not be able to get back to me for a while. He also told me that they would inform me of our destination and amount of time remaining once that had been determined.

In the meantime, I joined the cabin crew in the mid galley and informed them of our situation. We began securing our galleys and waking the passengers. Approximately fifteen minutes later I received an interphone call from Second Officer Chase Osborne informing me that we that we were in the process of dumping fuel and would be landing in Tehran in approximately fifteen minutes. I asked if the crew should prepare for a yellow or red level emergency. He confirmed with Captain Corby that we should prepare for a yellow level emergency and that we did not anticipate evacuating the aircraft upon landing. After informing the cabin crew, I began checking my Flight Attendant manual to review emergency procedures and making sure that we were not overlooking anything. The Captain then made a P.A, informing the passengers of our situation while the crew began preparing the cabin for our landing. Almost immediately a customer asked if they would still make their connection in Amsterdam!

On descent into Tehran I did not receive any reports from the cabin crew or observe any evidence of an escalating emergency. Strangely I did not feel nervous about the possibility of fire or what fate might befall us in Tehran. The calm and professional manner of the both the flight deck crew along with the response of the cabin crew reassured me that we would be able to handle whatever situation we would have to face. I felt personally prepared having just been to annual safety training in the prior month. The training this year focused on red level emergencies.

Upon landing in Tehran we were led off the runway by emergency vehicles. It was difficult to estimate how many vehicles met us but it had to be quite a few given the number of flashing red lights we observed. The customers remained in their seats and remained calm throughout the entire experience. Eventually air stairs were brought to Door 4 left and a man in uniform from Iran Air came up the aisle and began speaking with me in broken English and Farsi. I directed him to the Captain. When the Captain greeted him in Farsi, the man shouted “The Captain my brother, the Captain my brother”. At that point I felt that we were in for a positive experience on the ground in Tehran.

When it was determined that the passengers and cabin crew would disembark and proceed to the terminal, I was informed by Michele that the crew had already packed up all the cold mid-movie sandwiches and pretzels plus 20 liters of water and all the cartons of orange juice to take into the terminal. This was an excellent idea because many of the passengers had not taken the hot sandwich snack after departing Bombay due to the late hour of departure.

The airport buses, which took us to the terminal, were large and modern. The terminal, which I later learned, was new and had only been open a few months. We were directed up a flight of stairs to the passenger transit area. We immediately set up a small snack bar buffet on an information counter that was not being used. All the passengers from our flight were eagerly helping themselves to our offering. Standing back and surveying the situation I noticed a poster size framed photo of the Ayatollah Khomeini just above our improvised snack bar. In fact his picture was on nearly every wall of the terminal.

After cleaning up our snack service the crew and passengers settled down in chairs while some went off in search of telephones and to explore the transit area. The terminal was semi-dark and basically deserted at 5:30 am. As the sun rose over the mountains the terminal gradually came to life as shops and kiosks opened and Iranian passengers entered the transit area heading for outbound flights. Although we were not restricted in anyway from roaming about the large transit area, I did notice three or four men in black suits with walky-talkies and cell phones in hand keeping an eye on us. During this time I sought out all the business class passengers to personally assure them that KLM in Amsterdam would monitor our flight movement and if necessary would rebook them prior to our arrival in Amsterdam. This drew the attention of the main cabin passengers and I gave them the same information.

After an hour and a half in the terminal the passengers were getting restless and wondering about our departure and their connections. I had no way to communicate with our pilots who were out on the tarmac attending to the aircraft. I approached one of the men in black suits who had been watching us. He seemed to be in charge as the other men always approached him for conversation and information. He spoke very little English but I was able to make him understand that I wanted to speak to our Captain. His solution was to take me to the women who made the P.A.s in the airport. The only problem was she sat near the front entrance of the airport on the other side of immigration. As he led me through immigration in the opposite direction one of the immigration officers stopped us and said I couldn’t go through. A loud and lengthy conversation between the two ensued and the immigration officer made a phone call to a higher authority. The phone was then handed to the man helping me and he got permission for me to go through. I had the impression the man escorting me had a high rank at the airport. He was very kind and friendly and he tried to help me in every way possible.

The woman at the P.A. station spoke a little more English but was not able to connect me to our Captain. I asked her if she could connect me to the KLM office but there was no answer there. She then dialed Mr. Shofari who was in charge of maintenance for Iran Air. Mr. Shofari was fluent in English and said that his mechanics were at our airplane working with the Captain and they were going to call him in about thirty minutes. I was instructed to call him back and he would let me know the status of our flight.

I called him back an hour later using the cell phone of the man watching over us. He then told me the plane would be fueled, towed to the terminal and ready to go in thirty minutes. So one by one I informed the passengers that we would be ready to embark in thirty minutes. After an hour and half the plane had not moved and we were not ready to embark. The nice man who was watching us was not able to provide any further information and we could not reach Mr. Shofari by cell phone. A few passengers told me they could see luggage and cargo being off loaded from our aircraft. That did not indicate to me that we would be leaving any time soon but I kept my concerns to myself.

At this point I went to a telephone office and tried to call crew scheduling in Minneapolis. I figured that they could transfer me to the SOC who would know the status of our flight. However, in order to reach someone on the crew scheduling line one needs to use touch-tone dialing. The system in Tehran was not compatible with the USA so I was unable to reach anyone in crew scheduling. The Iranian women working at the phone desk did not charge me for the call. Returning to the man with the cell phone I was finally able to reach Mr. Shofari who said the plane would be fueled shortly but first they wanted to serve the passengers breakfast in the terminal. A catering truck from Iran Air pulled up to a nearby jet way and brought five meal carts into the terminal loaded with a cold breakfast snack, individual carts of OJ and large thermoses of hot tea. The cabin crew passed around the breakfast snack, served the OJ and tea to our 241 passengers and picked up.

After breakfast I was asked by my Iranian friend with the cell phone what type of security we wanted for the passengers prior boarding. He explained that they could give them an Iranian security screening or an international departure screening. I suggested that an international departure screening would be probably be best since we were going to a country outside Iran and they all agreed. It was necessary for the women passengers to go through a separate screening room while the male passengers were directed to another screening area. We were then directed to waiting buses to be driven back to the aircraft. It turned out that the aircraft was never brought to the terminal after all.

Returning to the aircraft we observed Second Officer Chase Osborne stationed on top of a fuel truck supervising the refueling. Once onboard we discovered that the Iran Air ground staff had cleaned the cabin, removed trash and replenished our ice supply. They asked us if we needed any additional cabin or catering supplies. Everyone we encountered in Iran was very kind and wanted to be as helpful as possible. A couple of airport officials said that Iranian people love Americans and America and apologized for the politics of their government. They said mixing politics, religion and government was not a good thing and they hoped that one day in the future relations would be better between our countries. I was surprised that they would be so open with their views but it left me with a very positive impression of the people and the country of Iran. Michele suggested that we serve breakfast immediately after take-off because the crew was concerned that the food might spoil since it was already 10 hours since our departure from Bombay.

Mr. Akin, one of our flight attendant managers, met us when we landed in Amsterdam. He told us after the passengers had deplaned that we must have done an excellent job because he never saw so many smiling faces and “thank yous” on a flight which operated on time much less our flight which was more than eight hours delayed. I would like to personally thank the flight attendant crew for their exemplary performance. It was an honor and privilege to work with:

- Dew Mennenga

- Michele Rockwood

- Terri Shanahan

- Angela Gordon

- Andrew Kuula

- Jessica Yeo

- Kanika Taneja (Interpreter)

Their focus on the care and feeding of our passengers allowed me the freedom to work with the Iranian officials in the airport and to keep our passengers in formed.