One of the more underexplored and deeply consequential aspects of financial digital mortgage marketing is the representation of credit product pricing, specifically interest rates, within organic search snippets. This area warrants close scrutiny not only because our own broker infrastructure explicitly supports the lawful presentation of rates — including embedding legally compliant rates in titles and metadata, which I’ll address in depth separately via an FAQ — but also because the deliberate or careless omission of required information in search results amounts to what we have long described and coined internally as "rate-bait". This is, in essence, a variant of click-bait aimed squarely at borrowers: a practice where an attractively low headline rate is positioned to lure borrowers’ attention, without the legally mandated accompanying disclosures.

Compliant Finance Advertising Explained: An article titled "Compliant Finance Advertising Explained"takes a dive into general advertising compliance, and it is supported by about 100 examples. We regularly look at the compliance and 'performance' issues associated with lower-performing, non-compliant, and often broken experiences offered by Broker Grow , BizLeads, Leadify, and other poor programs in one of our Facebook Groups  . Since launching the very first financial ad on Facebook a number of years ago, we've never published an ad that didn't meet all compliance obligations (and we've never had an ad account banned). Those organisations mentioned (among a number of others) are currently non-compliant, and all run the risk of ad account closure or compliance notice. Note: Broker Grow (formerly Karbn) has nothing at all to do with our extremely effective Broker Growth program, and we can only assume that they're leveraging a product name we've used for over 20 years to promote their far inferior product.

. Since launching the very first financial ad on Facebook a number of years ago, we've never published an ad that didn't meet all compliance obligations (and we've never had an ad account banned). Those organisations mentioned (among a number of others) are currently non-compliant, and all run the risk of ad account closure or compliance notice. Note: Broker Grow (formerly Karbn) has nothing at all to do with our extremely effective Broker Growth program, and we can only assume that they're leveraging a product name we've used for over 20 years to promote their far inferior product.

Ethical Obligations: It is a fundamental misunderstanding - and, regrettably, a dangerously common one - to assume that a mortgage broker’s Best Interests Duty (BID) springs into existence only at the point of a formal credit application or when the preliminary assessment is drafted. In truth, the obligation to act in the client’s best interests originates the moment a prospective borrower is first exposed to your representation — whether that exposure occurs through a website headline, a social media post, a sponsored link in a search engine, or the words of an offhand remark at a community seminar. This duty is not merely a statutory box to tick under the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 or ASIC Regulatory Guide 273 — it is a principle of professional conduct that binds us morally, ethically, and reputationally. The plain fact is that our profession now accounts for over three quarters of all new mortgage originations in Australia. We are no longer a fringe channel or a discretionary distribution option; we have become the primary conduit through which ordinary Australians gain access to housing finance. This centrality comes with consequence. By occupying the front line of mortgage advertising, we stand as both advisor and advertiser. We shoulder a higher burden than lenders alone because our role is not merely to promote but to interpret, to compare, to advocate, but to ensure that every impression we generate is accurate, balanced, and aligned with the consumer's best interests from the very first point of contact. Our marketing, therefore, must not only comply with the black letter of the law — it must exemplify the highest standard of truthfulness, transparency, and fitness for purpose. A misleading headline, an omitted comparison rate, an inappropriately targeted special product — these are not trivial infractions; they are betrayals of the trust our clients place in us as the keepers of their financial welfare. Best Interests Duty does not begin at the desk - it begins at the headline. And in a profession that now commands the trust of the overwhelming majority of Australian borrowers, we have no lesser responsibility than to hold ourselves, individually and collectively, to standards that equal - and wherever possible, exceed - those imposed upon the lenders themselves. Sadly, we're failing to accomplish what I've just described.

The legal position under the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) (NCCP Act) is unequivocal. Section 160 imposes a positive obligation: if a quoted interest rate appears in an advertisement in any medium it must be accompanied, with equal prominence, by a valid comparison rate. There is no exemption for metadata, no safe harbour for organic SEO content, and certainly no tolerance for disclaimers buried behind the click-through. The obligation applies to the representation as received by the consumer, not merely the landing page to which they are directed.

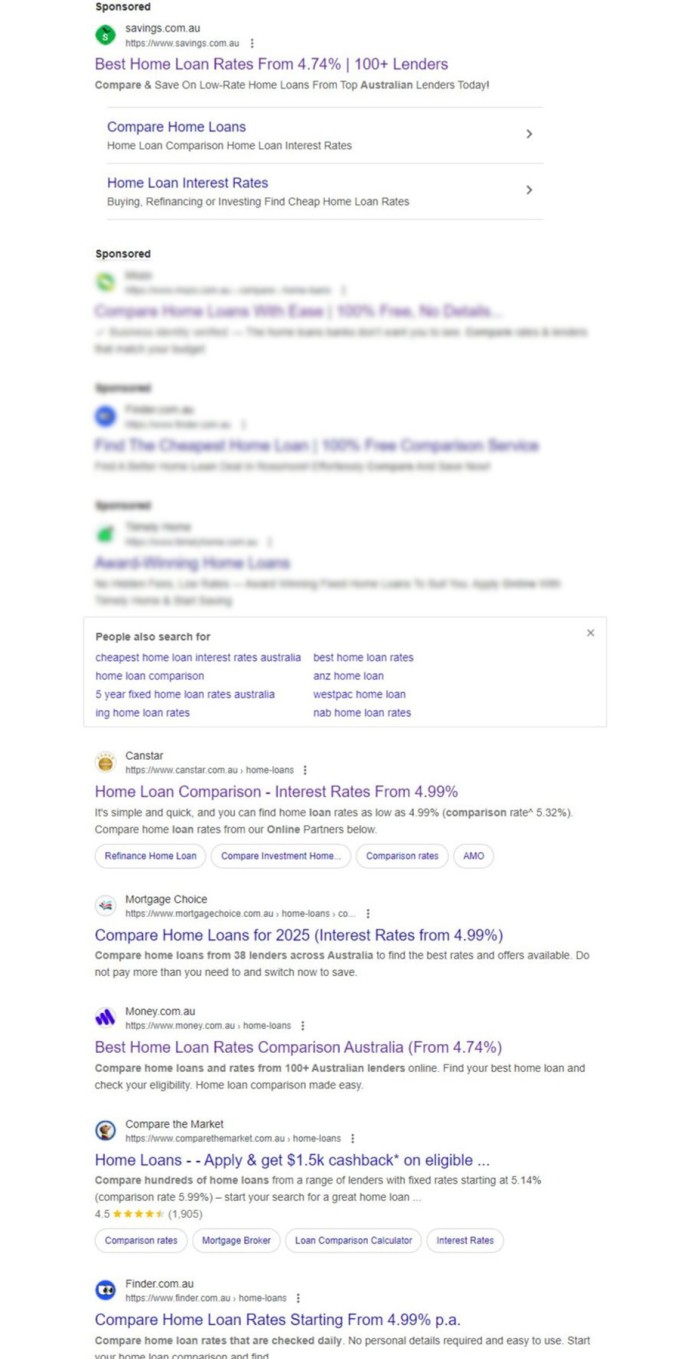

Pictured: In an era where 70–80% of borrower journeys begin with a digital search query, the obligation to ensure compliance extends to every word that might appear in a search engine results page (SERP) — whether paid (AdWords) or organic (SEO). Pictured is a search for various comparison websites.

Take the example that prompted this reflection: in the snapshot of Google search results I examined recently, for those that returned rate in their title, only a few managed to satisfy the statutory obligation by disclosing a comparison rate alongside the nominal rate. The remaining websites in the same space either omitted the comparison rate altogether or buried it beyond the visible snippet — which, in functional terms, means it does not exist for compliance purposes.

The Matrix API: An article that'll be published shortly on the Matrix API details how we crawl and index broker websites. Of the thousands of websites we crawl, about 80% are non-compliant in some way, half are blatantly non-compliant, and of those that show an interest rate in their title, around 96% are presented illegally.

Website Comparison & API: We've supported rate data, comparison data (via an API), and a standalone comparison website tool for a number of years. It should be noted that we go to significant lengths to ensure compliance, and we fill pages up with a large number of disclaimers.

ASIC Regulatory Guide 234 (Advertising financial products and services) is equally plain in its language: any representations about rates, repayments, or potential savings must be clear, accurate, balanced, and not misleading (in any way). The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), administering the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), reinforces these general prohibitions against misleading or deceptive conduct (ACL s18) and misleading omissions. Failure to disclose a key qualifying fact — such as the comparison rate that reflects true borrowing costs — is an omission that is both material and actionable.

An interesting question arises when we consider the technological and practical realities of SEO and SERP snippets. Is it even feasible to present a comparison rate with equal prominence in a 60–70 character title tag or meta description? Many digital marketers would argue it is not. But practicality is not a defence to statutory obligations — especially when the same law that demands a comparison rate also places a duty on the credit licensee to ensure all published materials are compliant in form and substance.

Further, under the Design and Distribution Obligations (DDO) regime, we have a positive obligation to ensure that any financial product is appropriately targeted and not promoted in a way likely to mislead a retail consumer. Using a niche or specialist rate — such as an eco or “green” loan — as a headline grabber without context is legally fraught. A green loan may be relevant for only a fraction of the population, and yet, presented without qualification, it can easily mislead the general audience into believing they qualify for that product when they almost certainly do not. This runs directly counter to both the spirit and letter of the DDO regime and the foundational principles of responsible lending or Best Interest Duty.

As a compliance strategist, I find the grey area of organic snippets particularly compelling. Although Google’s indexing and rendering of on-page data is outside the publisher’s direct control, the underlying source markup is not. It is well within the competence of any broker (or aggregator) to ensure that the crawled page text includes both the nominal and comparison rates, correctly marked up. If Google truncates or prioritises part of the title tag, that is a risk, but it does not relieve the publisher of the obligation to ensure the full text is legally compliant at source.

To be clear: under ASIC’s regulatory framework, organic listings can be treated as advertisements. If a search snippet displays an interest rate, that snippet is effectively an extension of the ad or offer. While the probability of enforcement for an isolated organic snippet breach is low, the legal risk is non-zero - especially if there is evidence of systematic intent to highlight a low, unqualified special rate as a means of attracting clicks that the advertiser knows will not be suitable for the general market.

In practice, the solution is straightforward: any representation of an interest rate - whether in site copy, title, description, or structured data - must be accompanied by the relevant comparison rate in a manner that, at minimum, satisfies the equal prominence test. Failure to do so is not merely sloppy marketing; it is potentially a statutory breach that exposes the licensee to regulatory sanction under the NCCP Act, the Corporations Act, and the ACL.

For brokers and aggregators, this is not an academic quibble. It is a practical reminder that your compliance obligations extend to every surface on which your rates are published or likely to be indexed. In the modern digital ecosystem, that means the visible page and the data behind it. If your rate is not suitable for the general audience, and you know the comparison rate would reveal that fact, you have a duty to disclose it. There's no navigating this simple requirement: an interest rate in isolation is illegal - it must always be paired with the associated comparison rate - not because it adds any value to the borrower outcome, but because it's the law.

Brokers and digital lenders must treat compliance as a front-end SEO concern, not merely a box to tick when the file reaches credit.

Broker Actions

If you're managing your digital presence yourself, consider the following list of actions when publishing rates in any location. If you've outsourced your digital presence, regularly review your website and digital footprint for basic compliance obligations.

- Always pair a headline rate with its valid comparison rate on every page. Include the full and complete Comparison Rate Warning on every page.

- Include both rates in the

<title>tag if possible - or at least ensure the first 60–70 characters include the mandatory details. - Use structured data (JSON-LD) responsibly: embed both rates so Google can index them.

- Avoid cherry-picking niche product rates as SEO bait for general audiences.

- Periodically audit your site’s snippets using

site:yourdomain.comin searches to check what Google is actually rendering. - Remember: your organic snippets are advertisements for NCCP and ASIC purposes.

- If you're going to include a limited-audience Green Loan, publish the title as something like "Green Home Loan 4.99% p.a. (5.43% comparison rate) | BrokerName".

- Confirm the promoted product aligns with the target market for the page’s expected audience.

- If a product is not suitable for most visitors, do not highlight its special rate prominently.

- Treat title tags, meta descriptions, and open graph text as advertising material — run them through your standard compliance sign-off process.

My Opinion

Where a licensee publishes a nominal interest rate in any form likely to be indexed by a search engine, the accompanying comparison rate must be embedded with equal prominence in the same HTML source. Failure to do so is an actionable contravention of the NCCP Act s160 and is likely to breach general prohibitions against misleading conduct under the ASIC Act and ACL.

Where a “green” or specialist rate is used to attract general borrowers, the omission of the qualifying context (including eligibility criteria) and the mandated comparison rate exacerbates legal risk and undermines DDO compliance.

There is no effective legal defence based on the argument that “Google cuts off the snippet”. The relevant test is whether the representation as made is likely to mislead the average consumer.

While the likelihood of an enforcement action for a single organic snippet is remote, repeated or systematic failures — especially for low, highly attractive specialty rates that function as rate-bait — create a trail of evidence supporting an inference of intent to mislead. This heightens legal exposure under Civil Penalties (Financial penalties under ASIC Act s12GB or ACL s224), Licence Conditions (potential conditions or sanctions for failure to maintain robust compliance frameworks), or Reputational Risk (breach of responsible lending principles).

Compliance with the letter of s160 is not a technicality. It is a core safeguard for truthful representation in Australia’s consumer credit market.

Don't play Russian roulette with your business. Stop the #finspam.